Microsoft is developing ‘hallucination experiences’ – at least according to certain sections of the media.

In late 2016, dozens of news outlets claimed Microsoft was either predicting, or developing, hallucinogenic VR. MailOnline declared that, “Microsoft says virtual reality could make you HALLUCINATE in the same way as LSD,” writing of VR’s “free-love, bongo-bashing vibe”. The source? A post on Microsoft’s blog presenting predictions from female researchers in order to inspire young people into STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) – which used the word ‘hallucinations’ in a metaphorical sense, and made no mention of LSD.

Look back to the birth of other new forms of media and you’ll see how quickly public sentiment shifts into moral panic. Victorians embraced telegrams for the purposes of commerce and government, then panicked at the idea of women sending telegrams to clandestine lovers. The rapid adoption of the telephone in the early 1900s was followed by fears it would lead to the demise of the ‘old practice of visiting friends’. When games consoles became commonplace in the 90s, that lead to hand-wringing that they could incite violence in young men.

The term ‘moral panic’ was defined by Stanley Cohen in the 60s as public alarm expressed in response to an issue that is regarded as threatening the moral fabric of society. More recently, Intel researcher Genevieve Bell built on Cohen’s theory by outlining the reasons some technologies (TV, the internet) lead to more panic than others (fountain pens, fax machines). Bell specified three areas to watch. If a new media technology affects our relationship with time, space and each other, then panic conditions are ripe. Which leads us back to VR.

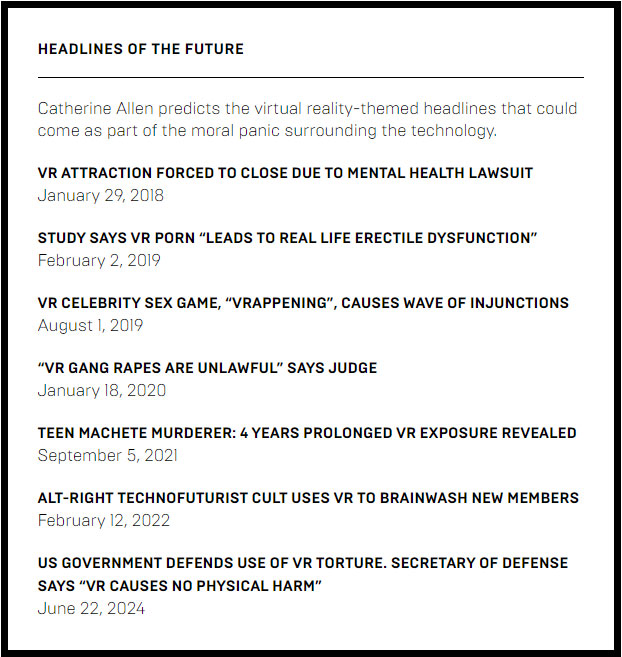

Those of us who work in VR might not want to admit it, but a moral panic is almost certainly coming – and as VR succeeds, it will grow. There’ll be a rash of VR-induced mental-health stories, ranging from post-VR panic attacks to episodes of psychosis. Then there’ll be concerns about addiction: what if the virtual world’s lack of limitation creates environments that are more enticing than the real one? Sex will be next – expect stories about teledildonic infidelity, lowered birth rates and lawsuits against unofficial sex experiences with CG versions of celebs. Following Bell, we might say that the underlying fear is that our bodies will become irrelevant slabs of flesh, existing purely for the purpose of keeping our brains alive.

“The first time I tried Batman: Arkham VR, I came out, looked at my hands and didn’t recognize them as my own”

It’s easy to dismiss these scare stories, but while moral panics are usually wildly exaggerated, they often stem from authentic concerns. Take the Great Cyberporn Scare of 1995, sparked when TIME magazine published a cover story on the hazards of ‘cyberporn’, citing an undergraduate study claiming that 83.5% of images on this new thing called the internet were pornographic. The methodology and reasoning may have been flawed, but there was an underlying concern which has played out into something valid. According to two NSPCC studies in 2015 and 2016, ten per cent of British 12- to 13-year-olds are worried they are addicted to porn, and most young people think that porn doesn’t teach consent.

The same goes for VR. I’ve seen all sorts of responses to immersion, ranging from quiet discombobulation to a frenzied screaming episode. I’ve actually experienced depersonalization of my own: the first time I tried Batman: Arkham VR, I came out, looked at my hands and didn’t recognize them as my own.

In the best-case scenario, the coming moral panic might encourage the VR industry to reflect constructively on itself. Early adopters can help steer towards this best-case scenario by seeing their role as the ‘critical friend’; helping reflection happen sooner rather than later. As for VR creators, they must take their role seriously and seek user input as early on in a product’s development as possible. They can also think carefully about the content they decide to produce, and how it might affect society in the long term.

It’s clear that VR is scary, exciting and powerful. It we treat this power with care then we’re far more likely to end up with an industry that not only weathers the storm ahead, but comes out stronger. And in the meantime, when you see a story about VR, don’t forget to question what you read.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.