Biomimetic glue: Put some mussel into it

Dr. Bruce Lee, an Assistant Professor of biomedical engineering at Michigan Technological University, is using a protein produced by mussels to create a reversible synthetic glue that not only can bond securely underwater—but also may be turned on and off with electricity.

“Biomimetic approaches [synthetic methods that imitate natural processes] have been used previously to develop materials for wet adhesion,” said Dr. Laura Kienker, Manager of ONR’s Biomaterials and Bionanotechnology Program. “The unique aspect of Dr. Lee’s research is that it aims to develop a biomimetic wet adhesive that can rapidly and repeatedly bond to, and separate from, a variety of surfaces in response to applied electrical current. There are both non-medical and medical applications of such a material for the Navy and Marine Corps.”

Like barnacles, mussels attach to rocks, docks and ship hulls—a natural occurrence called biofouling. Mussels secrete a combination of natural liquid superglues and stretchy fibers, called byssal threads, that works equally well in saltwater and freshwater; can stick to both hard and soft surfaces; and is strong enough to withstand the roughest sea conditions.

The secret behind mussels’ adhesive success is an amino acid called dihydroxyphenylalanine—DOPA, for short. A chemical relative of dopamine—the neurotransmitter that helps control the human brain’s pleasure and reward centers—DOPA is a critical ingredient in fastening the superglues and byssal threads to a location. It also enables mussel secretions to be both cohesive and adhesive—meaning they can adhere to themselves and other surfaces.

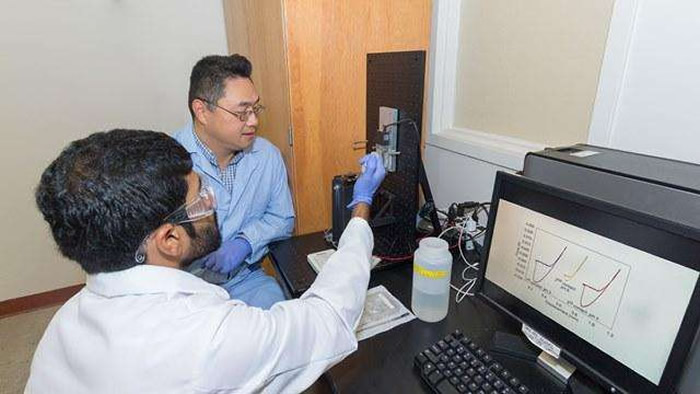

Lee and his research team blended DOPA with polymers such as polyester and rubber to create synthetic glue that holds together when wet. Laboratory tests demonstrated this material can attach to a variety of surfaces, including metal, plastic and even flesh and bone.

“One very valuable quality of this synthetic glue is its versatility,” said Lee. “We can change the chemistry to make it as rigid or flexible as we need—while still maintaining its overall strength and durability.”

Lee and his team are now trying to figure out how to use electrical currents to create a chemical “on-off” switch that temporarily changes DOPA molecules to make the synthetic adhesive sticky or non-sticky at will. So far, they’ve been able to accomplish this by tweaking the glue’s pH balance, but are still working to achieve this capability using electrical stimulation.

“This work is novel in the sense that there is no smart adhesive out there that can perform underwater,” said Lee. “The chemistry that we can potentially incorporate into the adhesive, causing it to reversibly bond and de-bond, is quite new.”

Lee envisions multiple uses for such a “smart glue”. It could bind underwater sensors and devices to the hulls of ships and submarines—or help unmanned vehicles dock along rocky coastlines or in remote locations.

There also are possible medical applications for an adhesive that can bind and un-bind at will. It could lead to new kinds of bandages that will stay attached when someone sweats or gets wet, and make it less painful to remove a dressing. The smart glue may even be used one day to attach prosthetic limbs and biometric sensors or seal surgical wounds.

For his adhesion efforts, Lee was named a 2016 winner within ONR’s Young Investigator Program, a prestigious grant awarded to scientists and engineers with exceptional promise for producing creative, state-of-the-art research that appears likely to advance naval capabilities.

More information: Office of Naval Research

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.