Non-toxic material generates electricity through hot and cold

Thanks to the discovery of a new material by University of Utah engineers of a non-toxic material that generates electricity, jewelry such as a ring and your body heat could generate enough electricity to power a body sensor, or a cooking pan could charge a cellphone in just a few hours.

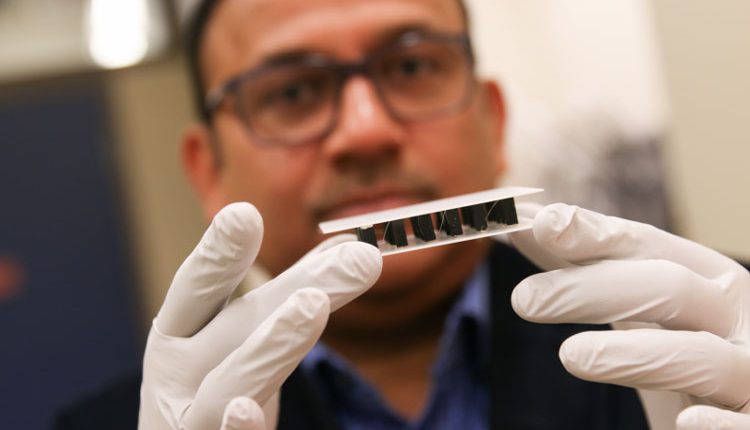

The team, led by University of Utah materials science and engineering professor Ashutosh Tiwari, has found that a combination of the chemical elements calcium, cobalt and terbium can create an efficient, inexpensive and bio-friendly material that can generate electricity through a thermoelectric process involving heat and cold air.

Their findings were published in a new paper March 20th in the latest issue of Scientific Reports. The first author on the paper is University of Utah materials science and engineering postdoctoral researcher, Shrikant Saini.

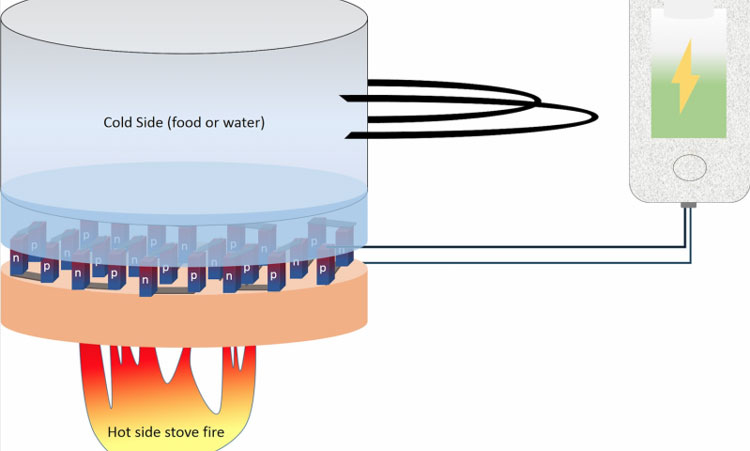

Thermoelectric effect is a process where the temperature difference in a material generates an electrical voltage. When one end of the material is hot and the other end is cold, charge carriers from the hot end move through the material to the cold end, generating an electrical voltage. The material needs less than a one-degree difference in temperature to produce a detectable voltage.

For years, researchers have been looking for the right kind of material that makes the process more efficient and produces more electricity yet is not toxic. There are other materials that can generate power this way, such as cadmium-, telluride- or mercury-based materials, but those are toxic to humans.

“There are no toxic chemicals involved,” he says. “It’s very efficient and can be used for a lot of day-to-day applications.”

The applications for this new material are endless, Tiwari says. It could be built into jewelry that uses body heat to power implantable medical devices such as blood-glucose monitors or heart monitors. It could be used to charge mobile devices through cooking pans, or in cars where it draws from the heat of the engine. Airplanes could generate extra power by using heat from within the cabin versus the cold air outside. Power plants also could use the material to produce more electricity from the escaped heat the plant generates.

“In power plants, about 60 percent of energy is wasted,” postdoctoral researcher, Saini, says. “With this, you could reuse some of that 60 percent.”

Finally, Tiwari says it could be used in developing countries where electricity is scarce and the only source of energy is the fire in stoves.

The Technology & Venture Commercialization Office of the University of Utah has filed a U.S. patent for the material, and the team will initially develop it for use in cars and for biosensors, Tiwari says.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.