These drones can do all kinds of tricks around obstacles

As consumer drone sales continue to rise, there has been an increase in companies and research groups developing obstacle-avoidance technology in order to minimize potential accidents.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the easiest technology to develop as it is challenging to develop real-time flight plans that avoid obstacles and can tackle unpredictable factors like wind and weather.

Researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have created software that allows drones to stop immediately and alter their paths, moving over, under, and around obstacles.

The team demonstrated how its drone technology works by avoiding 26 distinct obstacles in a simulated “forest.”

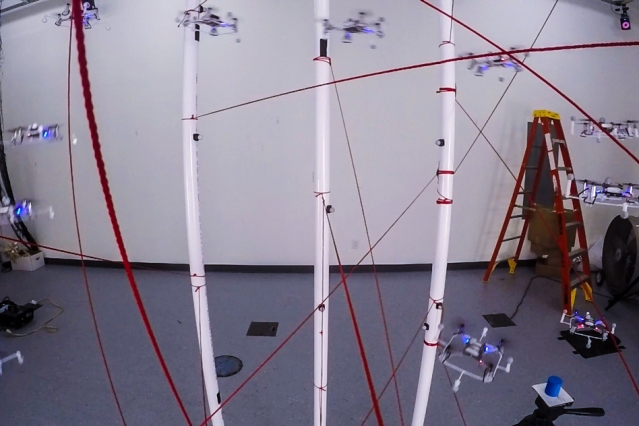

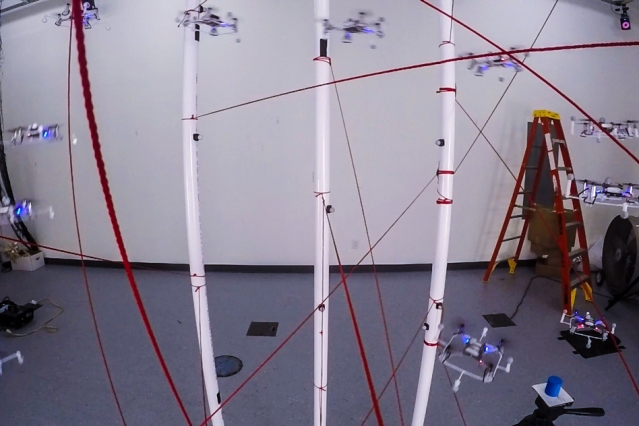

The above video shows MIT’s quadrotor doing donuts and figure-eights through an obstacle course of strings and PVC pipes. The drone weighs just over an ounce and measures at 3.5 inches from rotor to rotor. The drone can fly through the 10-square-foot space at speeds above 3 feet per second, according to MIT.

“Rather than plan paths based on the number of obstacles in the environment, it’s much more manageable to look at the inverse: the segments of space that are ‘free’ for the drone to travel through,” said Benoit Landry, recent MIT graduate, who was first author on a related paper just accepted to the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). “Using free-space segments is a more ‘glass-half-full’ approach that works far better for drones in small, cluttered spaces.”

The biggest challenge with technology of this nature is figuring out which methods can actually be used in real products, according to Landry.

“The best way to do that is to conduct experiments that focus on all of the corner cases and can demonstrate that algorithms like these will actually work 99.999 percent of the time,” said Landry.

Story via MIT.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.