For centuries, lenses have looked the same: thick, heavy pieces of glass carved and polished to bend light into focus. They work beautifully, but they weigh us down. Every camera, telescope, or satellite has been built around stacks of glass.

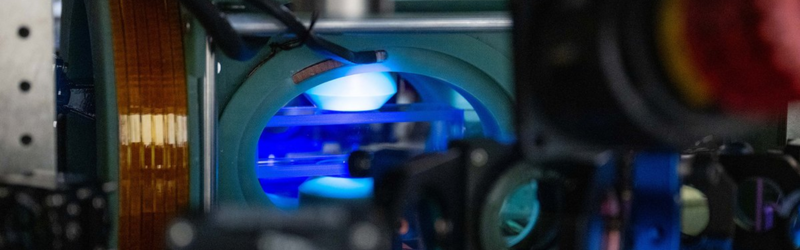

So when researchers began exploring “metalenses,” the idea felt almost too good to be true. Instead of heavy optics, you could use an ultrathin sheet of nanostructures to control light. The dream was a camera lens as thin as a piece of cling film. That kind of leap could change everything from drones to smartphones to satellites.

But progress slowed because the physics refused to cooperate. A single metalens could bend one color of light fairly well. Push it further, and the design started to break down. Try to handle multiple colors at once, or focus regardless of polarization, and you hit a wall. The single layer simply could not provide enough phase control to make it work.

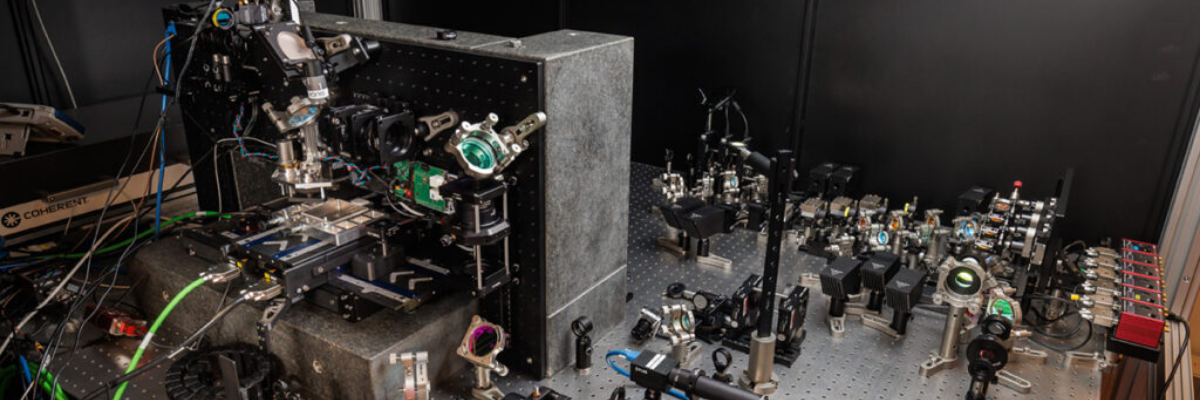

The team at ANU decided to change the question. Instead of asking one layer to do the impossible, why not divide the work across several layers?

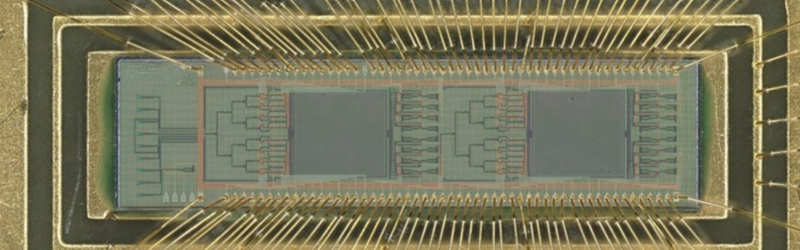

Their approach was to stack multiple metasurfaces, each patterned with nanostructures designed to handle part of the optical task. It is the same principle engineers often use when a single component cannot manage the load: spread the job out, and let each part do what it is best at.

Designing those nanostructures was no small feat. The team turned to inverse design methods that produced a library of unusual shapes: rounded squares, clovers, propellers. Each shape behaved like a tiny optical antenna, shifting light just enough to add the right phase delay. When stacked together, these layers could focus several wavelengths across a larger aperture, something no single surface could manage.

The breakthrough does not erase every challenge. The method tops out at about five wavelengths before diffraction and coupling effects take over. Fabrication also grows more complex because each layer must be aligned with extreme precision. But the gain is real. For portable imaging, drones, or satellites where every gram and millimeter matters, a stack of thin wafers looks far more attractive than a tower of glass.

What makes this story compelling for engineers is not just the outcome but the mindset. Instead of forcing one layer to solve every problem, the team treated the lens like a system of cooperating parts. By distributing the optical burden, they created a path forward for technology that had stalled.

The field of metalenses is still young. There are limits to overcome and new tricks to discover. But with this multilayer strategy, it feels like the work has entered a new chapter where light can finally be bent on our terms.

Read the full story: Tiny and powerful – metamaterial lenses for your phones and drones