For decades, silicon felt untouchable. It powered every charger, every power supply, every inverter worth mentioning. Designers knew its quirks, its limits, its sweet spots. It was comfortable—until Gallium Nitride showed up and refused to stay in the niche everyone assumed it belonged to.

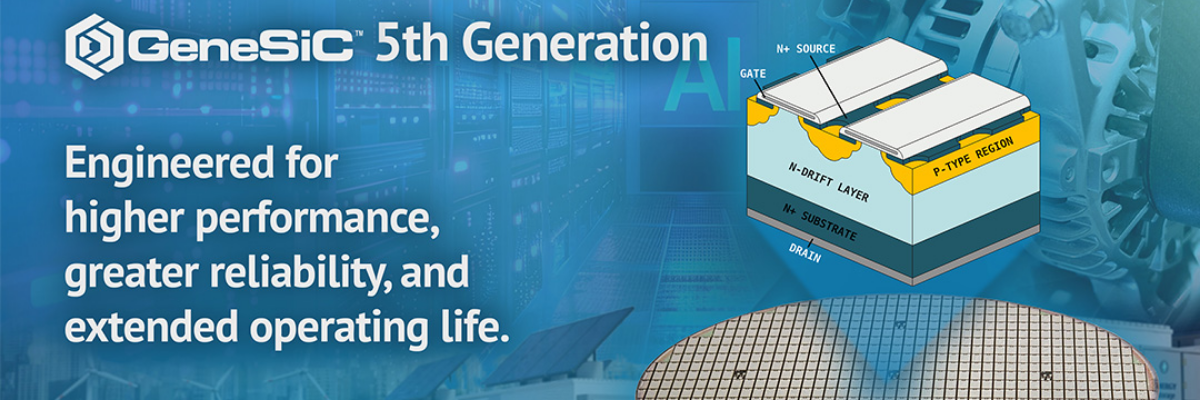

GaN’s rise didn’t come from hype. It came from physics quietly rewriting the expectations. A material that handles higher voltages and switches faster than silicon will always attract engineers who spend their days shaving losses off converters and fighting heat inside cramped enclosures.

The first time you watch a GaN transistor switch, it feels a little unfair—like it’s skipping steps. Less wasted energy. Lower capacitance. Faster edge rates. Suddenly the old silicon MOSFET that always did the job looks sluggish.

And the industry didn’t need long to put those advantages to work.

Take fast-charging power bricks. A standard silicon-based 65-watt charger used to be the size of a bar of soap, mostly because its lower switching frequency demanded bulkier magnetics and heavier thermal margins. The moment GaN chargers appeared, companies like Anker and Belkin released 65W adapters that were half the size, ran cooler, and could push more power in the same footprint. It wasn’t a gimmick. It was simply what happened when the switching losses vanished.

The same pattern is unfolding in data centers. High-efficiency server power supplies—especially 80 Plus Titanium units—are being redesigned around GaN FETs because squeezing out another percent of efficiency saves real money when you’re running tens of thousands of servers. A silicon design hitting 95–96% was once impressive. With GaN, engineers routinely push toward 97–98%, and the thermal relief alone changes the rack-level math.

Even automotive inverters and onboard chargers are leaning in. Not as loudly as the consumer charger market, but steadily. Anywhere the design pressure revolves around heat, switching speed, or size, GaN has become the material engineers reach for when silicon hits a wall.

Silicon isn’t going anywhere. It still rules the low-cost world. But the top end—the space where thermal limits and switching losses crush creativity—belongs to GaN now. And it didn’t need to make bold promises. It just needed to work better.