Micro Harmonics’ new WR-8 voltage-variable attenuator highlights a growing reality in mmWave system design: traditional attenuation approaches stop scaling once you push into the D-band.

At lower microwave frequencies, designers can usually reach for PIN-diode attenuators, resistive pads, or switched networks and move on. But at 90–140 GHz, those familiar techniques begin to fail—electrically, mechanically, and thermally. Loss becomes dominant. Repeatability suffers. Packaging parasitics take over. And tuning mechanisms often become the weakest link in the chain.

Micro Harmonics’ latest VVA addresses that problem not with a refinement of conventional techniques, but by switching to a fundamentally different mechanism: Faraday rotation.

Why Attenuators Become a System-Level Constraint in mmWave

Attenuators are often treated as secondary components—used for calibration, leveling, or protecting sensitive front ends. But in mmWave systems, attenuation accuracy and stability can determine whether a system is usable at all.

Designers working in:

-

D-band radios

-

Radar front ends

-

Sub-THz instrumentation

-

Scientific measurement platforms

-

Advanced comms research systems

are increasingly dealing with issues such as:

-

Excessive insertion loss from traditional attenuators

-

Limited power handling in semiconductor-based devices

-

Drift and non-repeatability with mechanical tuners

-

Fragile devices that cannot survive real-world handling

At these frequencies, even small parasitic effects from diode junctions, thin-film resistors, or packaging transitions can dominate performance. That’s where alternative physical mechanisms—like magneto-optic effects—start to make practical sense.

Faraday Rotation as an RF Control Mechanism

The WR-8 attenuator uses voltage-controlled Faraday rotation rather than semiconductor conduction to achieve tunable attenuation. While Faraday rotation is well-known in optics and physics, its use in mmWave RF components is still relatively niche.

The benefit is architectural: instead of relying on lossy semiconductor junctions inside the RF path, the attenuation mechanism is based on controlled rotation of electromagnetic polarization through a magnetically biased medium. That allows the device to behave more like a precision passive RF element than a traditional active attenuator.

Practically, that shows up in specs such as:

-

<1.0 dB average insertion loss across 90–140 GHz

-

No moving mechanical parts

-

Electrically tunable control

-

Stable RF characteristics across the band

At D-band, achieving sub-1 dB average loss across the full waveguide band is not a trivial accomplishment. Many conventional PIN-based or resistive approaches struggle to reach that performance without sacrificing tuning range or power handling.

Why Electrical Tuning Matters More Than Ever

One of the subtle strengths of this approach is that it delivers electrical tuning without mechanical wear mechanisms.

In high-frequency labs and deployed mmWave systems alike, mechanical attenuators remain common—but they come with tradeoffs:

-

Limited tuning speed

-

Mechanical drift over time

-

Wear-out failure modes

-

Sensitivity to vibration

Voltage-controlled tuning with no moving parts changes how the attenuator can be used. Instead of being a “set-and-forget” lab accessory, it becomes viable for:

-

Dynamic signal leveling

-

Automated calibration loops

-

Adaptive power control

-

Closed-loop instrumentation systems

That opens the door to more software-defined control architectures even at extremely high frequencies.

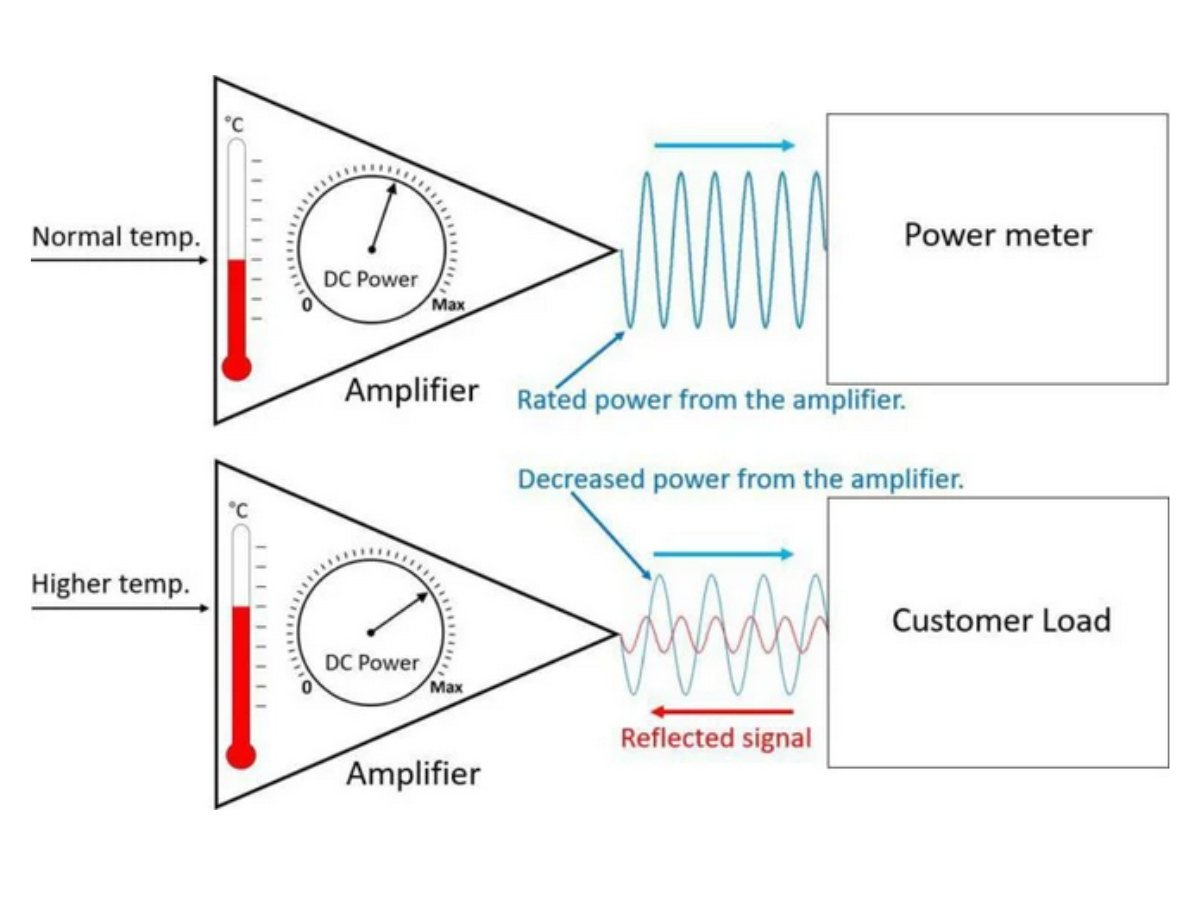

Power Handling Is Not a Footnote at 140 GHz

At first glance, 2.4 W of power handling might sound modest compared to lower-frequency components. But at 90–140 GHz, that figure is significant.

Many semiconductor-based mmWave components struggle well below that level, especially when insertion loss is already high. Power dissipation compounds quickly when losses climb into several dB. A low-loss device with multi-watt handling capability provides more headroom for:

-

High dynamic range measurement setups

-

High-power radar front ends

-

Experimental transmit chains

-

mmWave research platforms

This is one of those areas where loss, power handling, and reliability are tightly coupled—and improving one usually forces tradeoffs in the others.

Waveguide Integration Reflects Real Deployment

The availability in WR-6.5, WR-8, and WR-10 configurations signals that this product is not targeting casual experimentation. These are the waveguide bands engineers use when they are already deep into mmWave system development.

The fact that the device is:

-

Waveguide-integrated

-

Fully characterized on a VNA

-

Delivered with measured S-parameter data

also signals the intended user: engineers building real RF chains who need confidence in how a specific unit behaves, not just typical datasheet curves.

At these frequencies, unit-to-unit variation matters. Providing individual characterization data is not just a convenience; it’s often necessary for system-level calibration.

Where Traditional Attenuators Fall Short

The announcement directly calls out the limitations of PIN-diode and resistive attenuators.

At mmWave frequencies, those technologies often suffer from:

-

Excessive series resistance

-

Packaging parasitics

-

Poor flatness across wide bandwidths

-

Limited power handling

-

Thermal sensitivity

Designers who have tried to push conventional attenuation techniques into the D-band often end up spending more time compensating for the attenuator than benefiting from it.

A fundamentally different physical mechanism—like Faraday-based attenuation—sidesteps many of those constraints rather than fighting them.

The Bigger Picture: mmWave Components Are Splitting Into Two Worlds

This product also highlights a broader industry trend.

At lower frequencies, RF components are converging toward high integration, silicon-based solutions, and digitally assisted calibration. At very high frequencies—above 90 GHz—the opposite is happening. Engineers are increasingly forced to adopt:

-

Specialized materials

-

Physics-driven mechanisms

-

Precision waveguide structures

-

Custom-fabricated devices

Micro Harmonics’ VVA sits squarely in that second category. It’s not trying to be cheap, mass-produced, or highly integrated. It’s trying to be physically correct for a frequency range where shortcuts no longer work.

The Takeaway for Engineers

If you are designing below 40 GHz, this product probably doesn’t matter to you. But if you are working anywhere near D-band, it highlights an important reality:

You cannot rely on scaled versions of microwave design techniques forever.

As systems push higher in frequency, success increasingly depends on:

-

Understanding the underlying physics

-

Selecting mechanisms that scale with frequency

-

Choosing components that were designed specifically for that regime

Micro Harmonics’ WR-8 voltage-variable attenuator is a good example of that shift. It’s not an incremental improvement on existing attenuator designs. It’s a recognition that at 90–140 GHz, the problem itself has changed.

And so must the solution.