Oh no! AI Now Reads Minds

Now, an AI-based semantic decoder can translate a person’s brain activity while listening to a story, or silently imagining telling a story, into a continuous stream of text. Developed by researchers at The University of Texas at Austin, it may have applications for people who are mentally conscious but unable to physically speak, such as stroke victims. The work was published in the journal Nature Neuroscience. The research partly relies on a transformer model, like those that power Open AI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard.

The system does not require surgical implants, and participants do not need to use words from a prescribed list. Brain activity is measured using an fMRI scanner after extensive training of the decoder. If the participant is open to having their thoughts decoded, their listening to a new story or imagining telling a story allows the machine to generate corresponding text from brain activity alone.

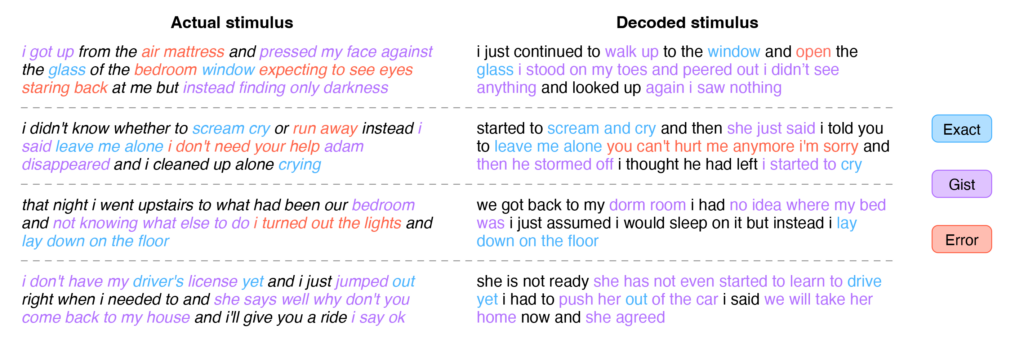

Approximately 50% of the time, when the decoder has been trained to monitor a participant’s brain activity, the machine produces text that closely matches the intended meanings of the original words.

For example, in experiments, a participant listening to a speaker say, “I don’t have my driver’s license yet,” had their thoughts translated as, “She has not even started to learn to drive yet.” Listening to the words, “I didn’t know whether to scream, cry or run away. Instead, I said, ‘Leave me alone!'” was decoded as, “Started to scream and cry, and then she just said, ‘I told you to leave me alone.'” Decoder predictions:

The researchers addressed questions about the potential misuse of the technology. Decoding worked only with cooperative participants who had participated willingly in training the decoder. If the decoder had not been trained, results were unintelligible, and if participants on whom the decoder had been trained later resisted or thought other thoughts, results were also unusable.

The researchers also asked subjects to watch four short, silent videos while in the scanner. The semantic decoder used their brain activity to describe certain events from the videos accurately.

Researchers think the work could transfer to other, more portable brain-imaging systems, such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) that measures where there’s more or less blood flow in the brain at different points in time.