By harnessing the channels trees use to move water between their roots and leaves, a team of University of Maryland researchers thinks it can harness body heat to provide energy using charged channel walls and other unique properties of wood’s natural nanostructures. The wood is transformed into a flexible membrane that generates energy from ions, which is what the human body runs on. A small temperature differential can be used to efficiently generate the ionic voltage.

Using basswood, a fast-growing tree with low environmental impact, they treated the wood and removed two components – lignin, that makes the wood brown and adds strength, and hemicellulose, which winds around the layers of cells binding them together. This gives the remaining cellulose its signature flexibility. This process also converts the structure of the cellulose from type I to type II which is a key to enhancing ion conductivity.

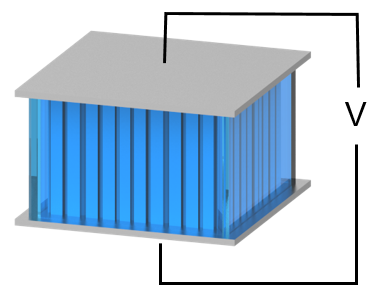

A membrane, made of a thin slice of wood, was bordered by platinum electrodes, with sodium-based electrolyte infiltrated into the cellulose. The regulate the ion flow inside the tiny channels and generate an electrical signal.

“The charged channel walls can establish an electrical field that appears on the nanofibers and thus help effectively regulate ion movement under a thermal gradient,” said Tian Li, first author of the paper.

“We are the first to show that this type of membrane, with its expansive arrays of aligned cellulose, can be used as a high-performance ion selective membrane by nanofluidics and molecular streaming and greatly extends the applications of sustainable cellulose into nanoionics,” said Li.

Previous UMD research to develop high impact applications of modified wood has included advances in creating a super wood 12 times stronger and “10 times tougher” than most metals, a sliver-thin, tin-coated wood battery, and a transparent wood windows that are cooler than glass and only slightly less transparent.

Lingbing Hu and his team of UMD researchers published the results of their studies in Nature Materials recently.

Source: University of Maryland