Handheld device changes shape to help sighted and blind navigate better

An engineer from Yale University has created a shape-shifting navigation device for both the sighted and visually impaired populations — basically everyone.

Adam Spiers, a postdoctoral associate in the robotics lab of associate professor Aaron Dollar, worked on a London-based interactive production of “Flatland.” The production took place in an old church where both sighted and visually impaired audience members were kept in complete darkness most of the time as they wandered through the space four at a time and a speaker narrated and sound effects told the story.

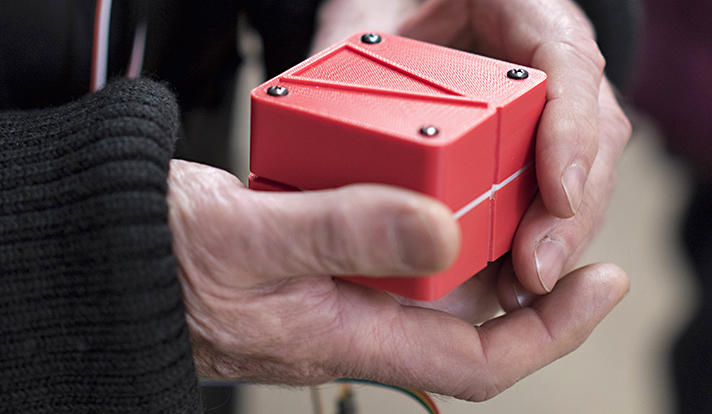

This is what sparked the development of a new navigation device. Spiers designed 3D-printed shape-shifting cubes to navigate the attendees through the darkness. The user’s position in the environment determined the shape of the wireless device. The top half of the cube twists in order to direct users toward the next destination and extends forward to indicate the distance to reach it.

So, instead of looking at a device to find your way, you can feel the change of the shape and know where to go.

“The simple idea is that when you’ve arrived at your target destination, it becomes a little cube again,” said Spiers, who specializes in the field of haptics, the sense of touch.

Spiers originally named the device the Haptic Sandwich, but is now leaning toward Animotus, the name that it took on in the “Flatland” story.

According to the engineer, said building the device took some trial and error because there was little precedent for it.

“Shape-changing is pretty new in haptics, so not a lot of people have done it before,” he said.

He thinks that his new invention has the potential to guide pedestrians and hikers while allowing them to appreciate their surroundings. He envisions hooking it up to Google Maps and letting the possibilities unfold.

Spiers opted for this new method, especially for the visually impaired because too many haptics-based devices rely on vibration which can get annoying. Devices with audio cues can be even more distracting, especially for people with visual impairments.

“Sound is pretty much how they appreciate the world,” he said. “If you visit a city, you look around and you get an impression. That’s what visually impaired people do also, but with audio.”

Some unexpected results emerged during the production, including how users reacted to the device. For the final scene, audience members were guided to one spot, where the devices were “confiscated,” followed by the sounds of the devices being destroyed.

“Some people found this very upsetting,” Spiers said. “It’s about 40 minutes that they were in there with the Animotus, so they got pretty emotionally attached to it.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.