Researchers create brighter displays that use less energy

Manufacturers are constantly looking for ways to brighten colors and images for flat-panel displays while using less electricity. Now a team of researchers from Sandia National Laboratories has developed a method that makes this possible.

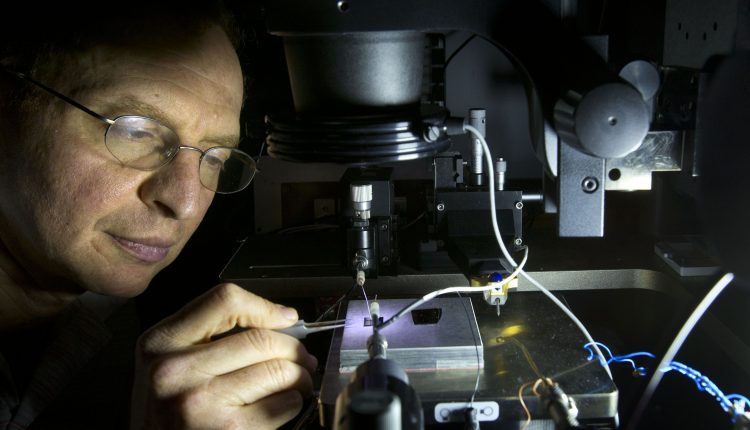

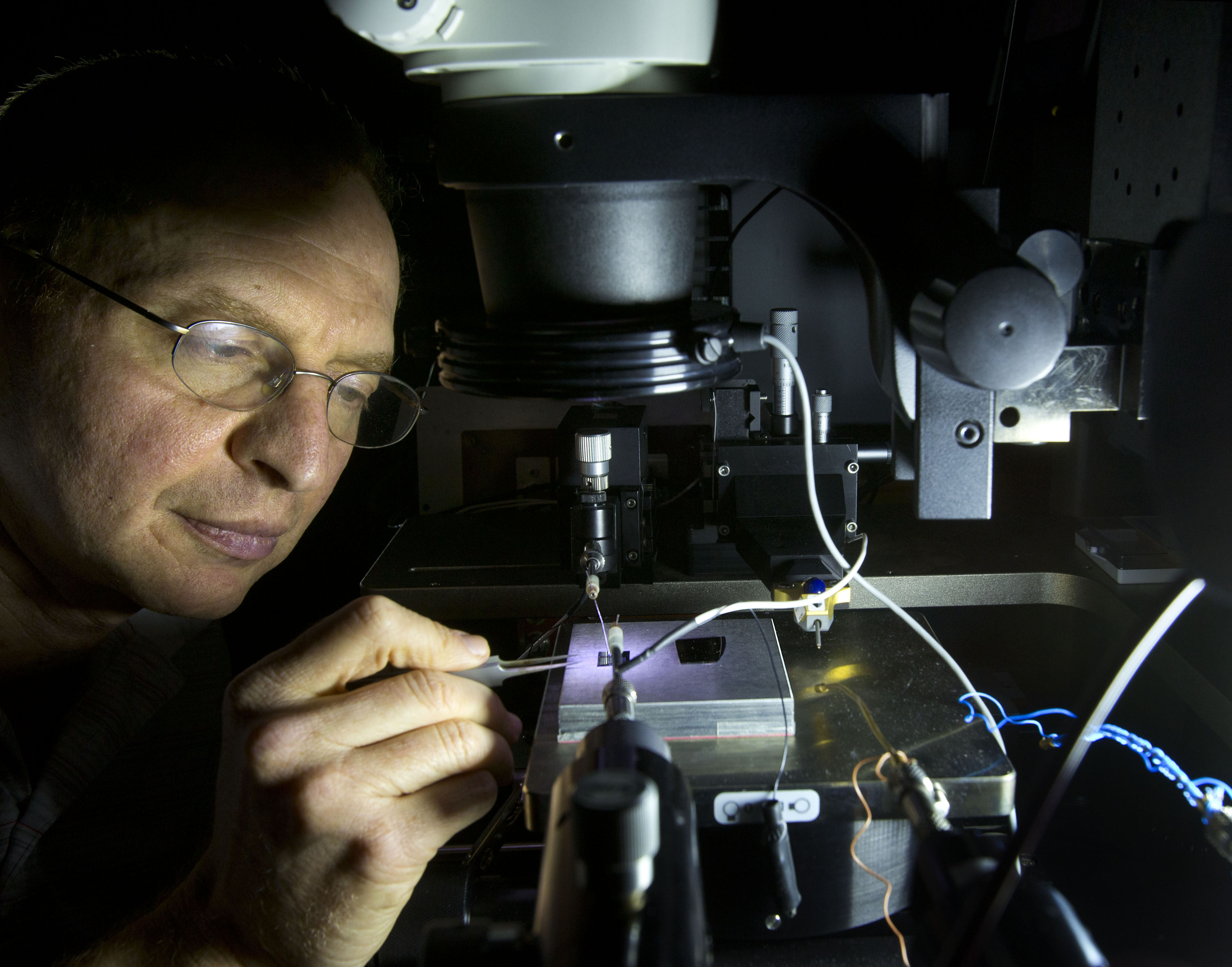

Alec Talin, along with researchers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology used super-thin layers of inexpensive electrochromic polymers that create bright colors and can be rapidly altered.

While electrochromic polymers are not new, the researchers are the first to figure out how to switch electrochromics on and off in the milliseconds required to create moving images.

Traditional electrochromic displays require thick polymer layers to obtain good contrast between bright and dark pixels, but that also require long diffusion times for ions and electrons, which only make them useful for static displays or darkening windows. Before now, there would be no use for them in the milliseconds needed for a movie. In addition, a full color display would require three different polymers.

The researchers overcame this problem by creating arrays of vertical nanoscale slits that are perpendicular to the direction of the incoming light. The slits were cut into a thin aluminum track that was coated with an electrochromic polymer and when light hit them, it was converted into surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs). SSPs are electromagnetic waves that contain frequencies of the visible spectrum that travel along the dielectric interfaces.

The distance between the slits in each array corresponded to the wavelengths of red, green and blue light. And the distance information was transmitted down through the array, and traveled along the interface between the thin polymer layer and the aluminum substrate.

The polymer was just nanometers thick, so it required very little time to change its state of charge — and therefore its optical absorption of colored light.

“These very inexpensive, bright, low-energy micropixels can be turned on and off in milliseconds, making them fit candidates to provide improved viewing on future generations of screens and displays,” said Talin. “The nanoslits improve the optical contrast in a thin electrochromic layer from approximately 10 percent to over 80 percent.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.