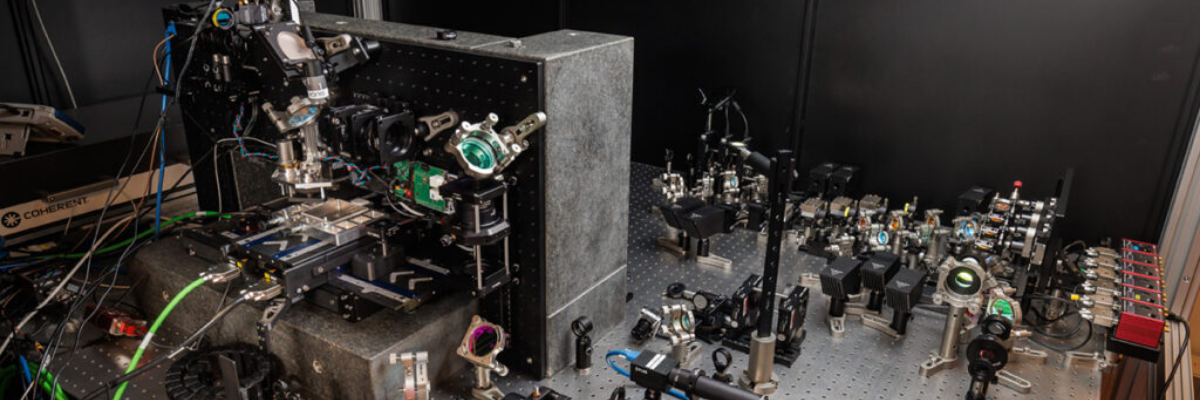

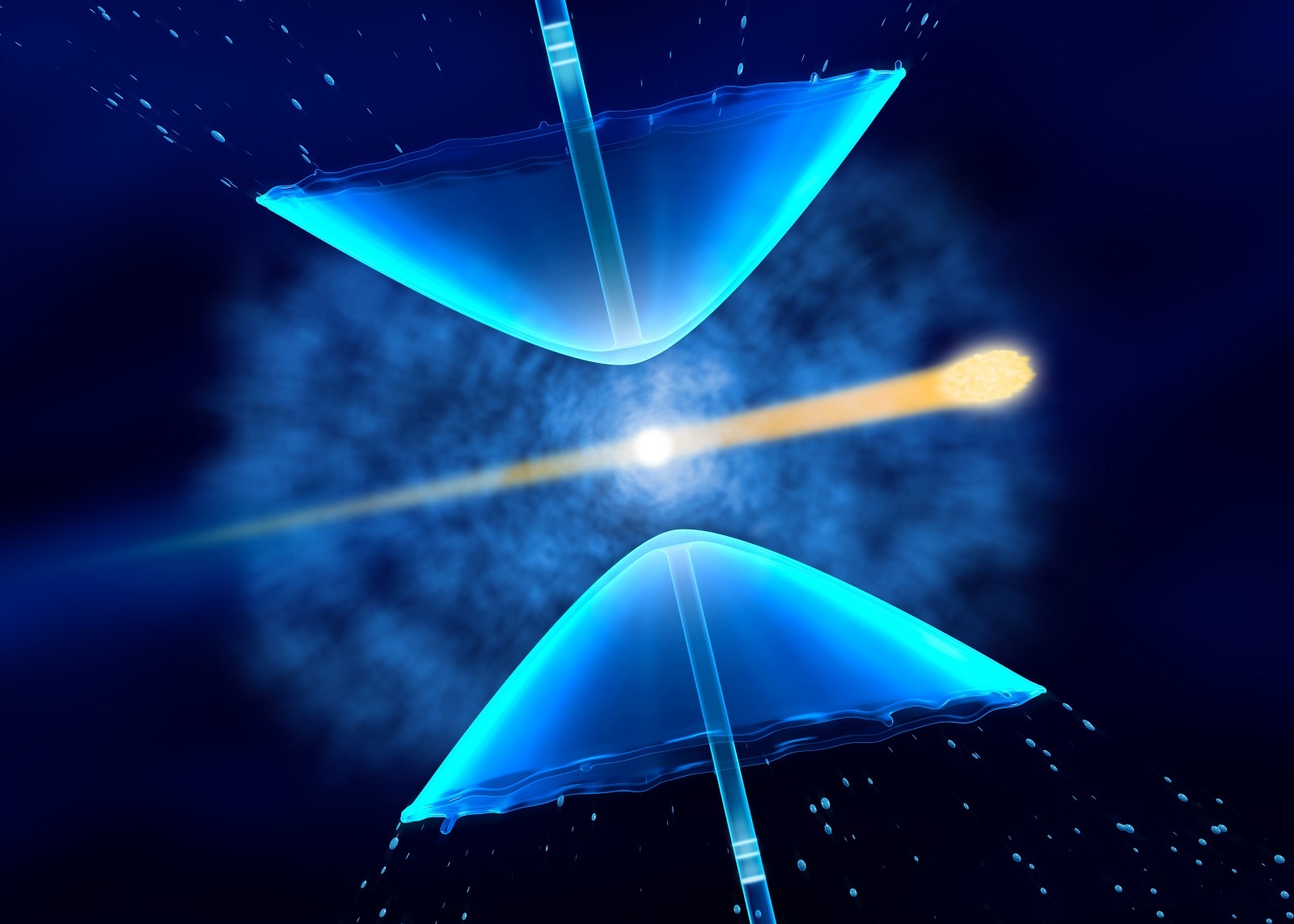

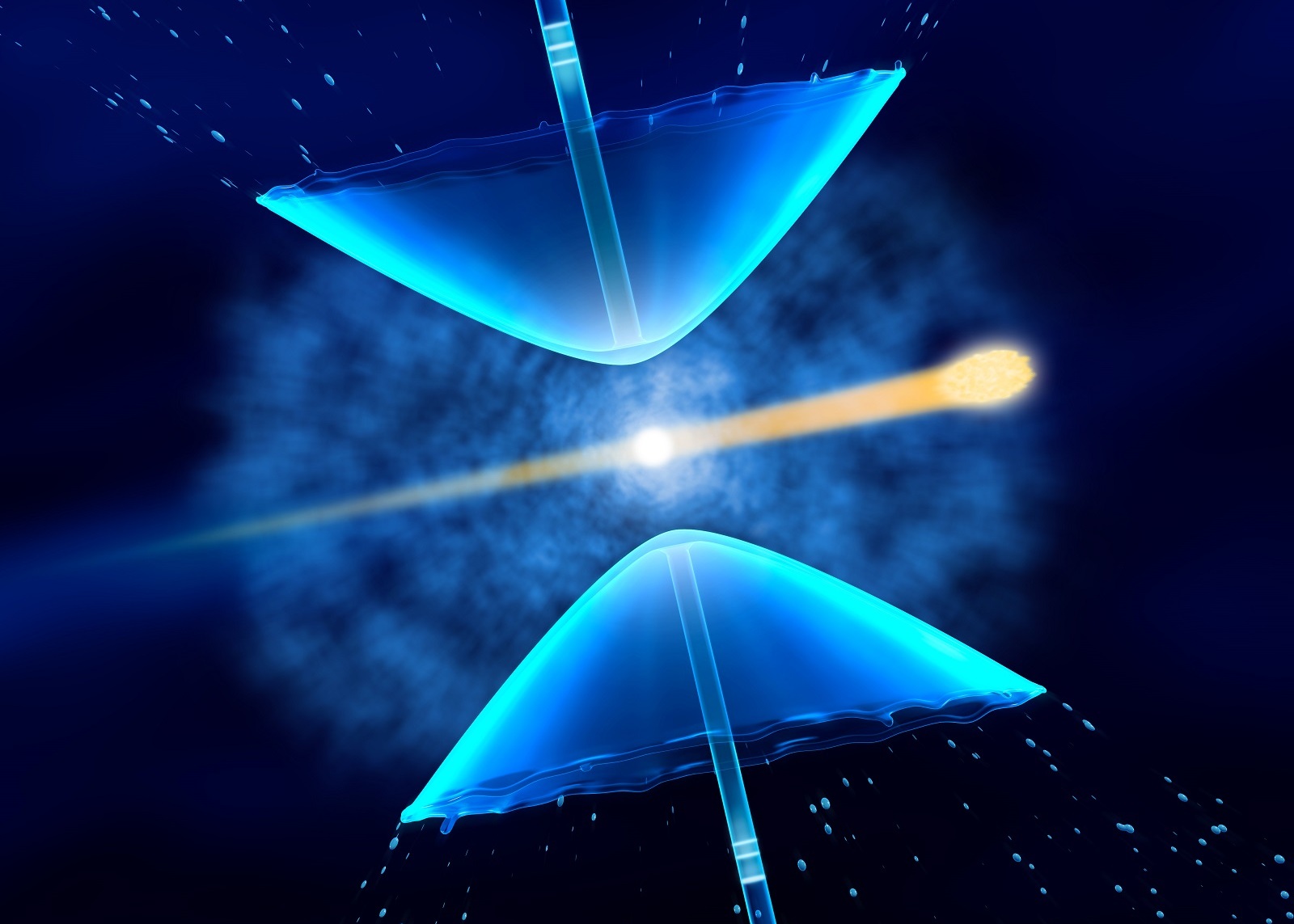

Researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have made the first microscopic movies of liquids getting vaporized by the world’s brightest X-ray laser. The video doesn’t only make for a visually appealing movie, but the data retrieved from it could lead to better experiments using X-ray lasers, which emit bright, fast flashes of light that take atomic-level snapshots of some of nature’s speediest processes.

Their new studies, portrayed in a series of videos, show in microscopic detail how the explosive interaction unfolds and provides clues as to how it could affect X-ray laser experiments.

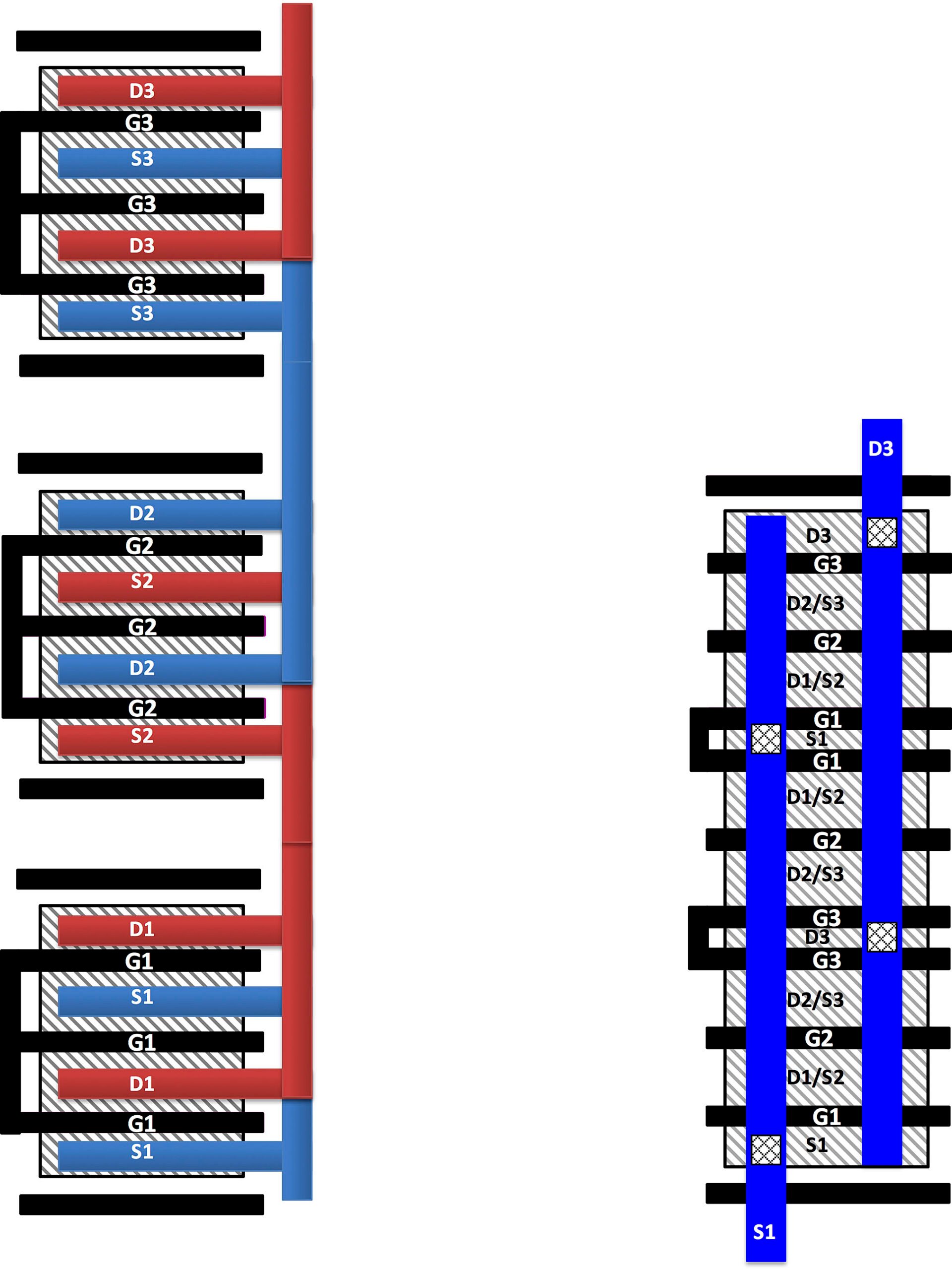

The team looked at two ways of injecting liquid into the path of the X-ray laser, as proposed by prior Stanford University research: as a series of individual drops or as a continuous jet. They strung hundreds of snapshots together into movies.

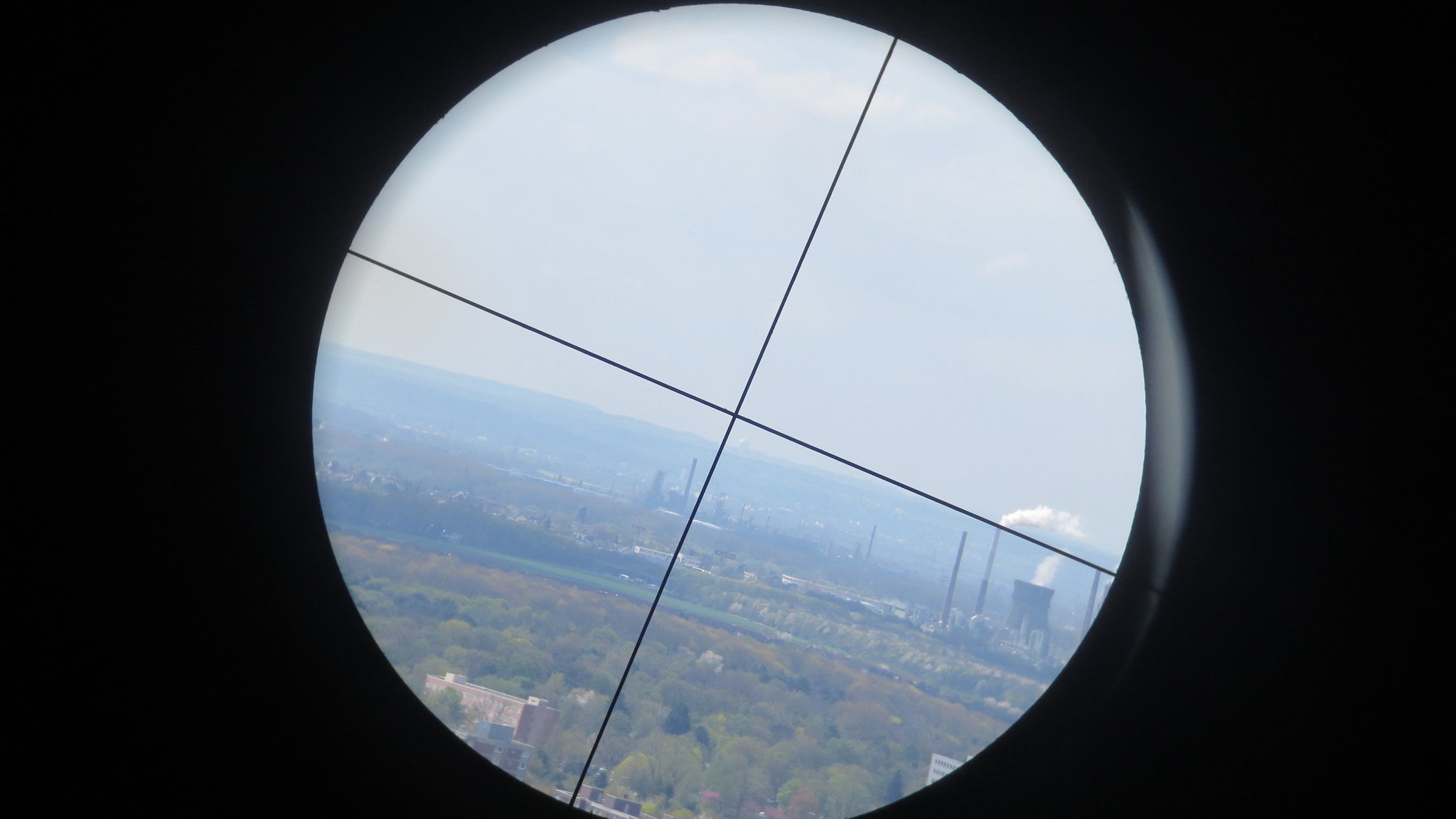

“Thanks to a special imaging system developed for this purpose, we were able to record these movies for the first time,” says Sébastien Boutet, co-author of the study from LCLS. “We used an ultrafast optical laser like a strobe light to illuminate the explosion, and made images with a high-resolution microscope that is suitable for use in the vacuum chamber where the X-rays hit the samples.”

The footage shows how an X-ray pulse rips a drop of liquid apart. This generates a cloud of smaller particles and vapor that expands toward neighboring drops and damages them. These damaged drops then start moving toward the next-nearest drops and merge with them.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.